Five Evidence-Based Study Strategies Your Students Should Be Using

Spring and early summer brings tests and exams for many students and teachers. If you’ve managed to cajole your kids into putting in some time outside of lessons, congratulations!

The bad news, though, is that left to their own devices, most students will be using ineffective study methods, meaning they will fall short of the marks and grades they could otherwise have hit.

The good news is that there are some simple evidence-based strategies that can transform how effectively your students study, and the grades they are therefore able to achieve. Read on to find out how.

- Retrieval practice: memory training

After almost a century of research, the results are in: there is now broad consensus among learning science researchers that the best study techniques are based on “retrieval practice” (see

here or

here for reviews). Most students study by pushing information into their brains – re-reading, highlighting, summarising, making notes – retrieval practice flips that on its head, and says they should be spending as much time as possible trying to pull information out of memory, trying to remember it.

There are plenty of options for using retrieval practice to study for tests:

- Training with flashcards

- Answering “quiz” questions

- Writing down all you can remember about a topic on a blank sheet

- Having a friend / family member test you

The key is to move on from the “pushing information in” stage sooner than feels comfortable, and spend as much time as possible studying by trying to remember what you know. It feels like harder work, but it’s far more effective.

Formative assessment is also a great discipline to use in your classroom as starter or exit activities: Science In The City has plenty of

assessment resources available to life a bit easier.

2. Spaced learning: conquer “forgetting”

Over time, we all forget what we once knew – even if we used retrieval practice to learn it! Spaced learning is the solution: for every new occasion on which your students revisit a fact or concept, their memory of it gets stronger and more permanent.

Try and get your students in a “little and often” habit: rather than cramming all the day before a test, far better to spread that same amount of study time out (or even do slightly less!) over a longer time, e.g. 10 minutes a day for a couple of weeks, rather than two hours the night before.

They will not only perform better on that test, but their knowledge will be much more secure, helping them build on it in future, rather than having to start seemingly from scratch in each new school year.

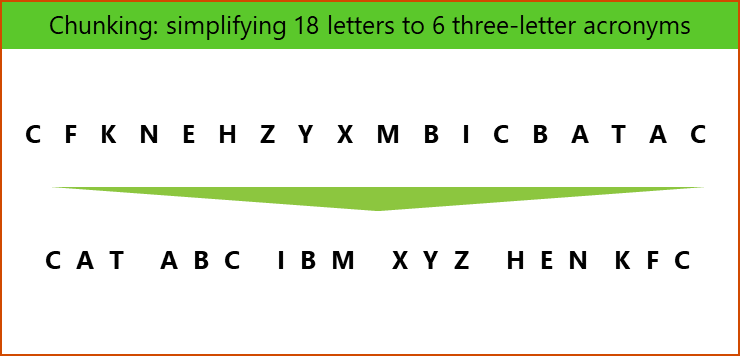

3. Chunking: data compression for memory

“Chunking” is the act of grouping a larger number of units of information – letters, words, phrases, numbers – together in meaningful ways to create a smaller number of units, making the information easier to remember. It’s your brain’s version of data compression algorithms that make files smaller for storage in computer memory.

Here’s an example of chunking in action: 18 random letters are very hard to remember, but re-order and add some grouping, and it becomes much easier.

You probably remember your own phone number by “chunking” the digits into groups. When someone else groups the digits differently, it can be hard to recognise even your own number!

Chunking is at the root of a many mnemonic techniques, such as:

Acronyms: making a new word from the first letters of the words you’re trying to remember, e.g. “HOMES” for the five Great Lakes (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior)

Acrostics: making a memorable phrase from the first letters of words you’re trying to remember, e.g. “My Very Excellent Mother Just Made Us Nine Pizzas” for planets

Chunking numbers with patterns: look for arithmetic relationships to make digits more memorable. Thulium was discovered in 1879: you can derive the “7” and “9” by subtracting and adding the “1” to the “8”, respectively.

You could spend a moment in lessons working with your students to come up with a novel chunking strategy, which not only helps them learn the content, but trains them in how to use chunking for themselves. See here for an in-depth guide to using a number of useful

chunking strategies, with more inspiration on how to apply the technique to a range of information types.

4. Dual coding: we are all visual learners

Have you heard of “learning styles” – visual, auditory, kinaesthetic? You may also have heard that there is

very little scientific evidence that teaching in each individual’s preferred style helps them learn.

However, it seems while we all have our preferences, we all have a bit of every “learning style” in us, and that appealing to multiple styles at once can

help us to learn.

The idea of dual coding is that by taking in information as both words AND a diagram / picture, you’re more likely to remember it – perhaps because you’ve got two different ways to remember that information when you get into the test.

If your students are making summaries ahead of an upcoming test, they might like to use a picture AND a description in words for key concepts, to help solidify their understanding and memory.

5. How to read (no, really…)

OK, so this is more about test-taking than studying: but how many times have you seen students throw away marks by not reading the question accurately?

When we read, our eyes move in jumps called “saccades”, with a focus point every few words. The brain fills in the words in peripheral vision based on word shape and context. That makes it very easy to miss things, especially under the pressure of a test!

If you know what you’re looking for, it’s painfully obvious, but if you don’t, a lot of people won’t spot the two “As” before “single step”.

In one example where students were taking test questions, researchers found that emphasising a key command word in a question by switching to a bold typeface increased the proportion of correct answers from 8% to 31%. That’s huge!

You may not be able to change the test papers, but there’s a simple solution: train your students in the disciple of reading questions slowly, deliberately and methodically, using their pen to underline key words in the question to add emphasis for themselves – to make sure they pick up every mark they deserve.

Wishing you and your students every success in any upcoming tests and exams!

****

This is a guest post for Science In The City by William Wadsworth, a Cambridge-trained psychologist and full-time study skills researcher, writer, coach and

author. He hosts the weekly

Exam Study Expert podcast and blogs at

www.ExamStudyExpert.com, both packed with tips to help students score the best possible grades, by unleashing the new science of truly effective independent study techniques.